Front Cover Back Cover

DUST TO DUST

A Doctor's View of Famine in Africa

David Heiden

Temple University Press, Philadelphia 19122

Copyright 1992 by Temple University

All rights reserved.

This book is dedicated to my parents,

Herbert and Natalin Heiden,

and to my wife Katherine Seligman.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

PROLOGUE

A World Away

CHAPTER ONE

SNAKES, SCORPIONS, AND THE FIRST PLAGUE

Fau 3 Refugee Camp, March 2-March 25, 1985

CHAPTER TWO

CONTROL AT A PRICE

Fau 3 Refugee Camp, March 25-April 20, 1985

CHAPTER THREE

THE RESPITE

Vacation in Gedaref, Kassala, Suakin, and Port Sudan,

April 22-April 29, 1985

CHAPTER FOUR

DEPARTURES AND DISLOCATIONS

Wad Kowli Refugee Camp and Khartoum,

April 30-May 24, 1985

EPILOGUE

TWO YEARS AFTER

Khartoum, Ghirba, Sefawa, and Tukulubab,

March 3-April 15, 1987

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book has taken five years, and although my name appears alone on the cover, it never would have happened without help from many people.

I initially conceived of this project as a picture story. Many people, but particularly Bill Jay and Bruce Davidson, finally convinced me that I needed to write what happened. Nevertheless, the photos have been the part most alive to me. I'm indebted to many photographers who generously reviewed proof sheets, work prints, slides, or other forms of the work: Katy Raddatz, Nick Nichols, Chris Killup, Arnold Newman, Linda Conner, Ken Light, Mary Ellen Mark, Michele Vignes, Naomi Weissman, Janet Delaney, Doug Menuez, Eugene Richards, Lois Conner, Fred Woodward, Matt Mahurin, Mike Rosen, Fred Richin, John Issacs, Abigail Heyman, Bedrich Grunzweig, Ruth Lester, Sandra Eisert, Stu Levy, Takeshi Yuzawa, Debra Heimerdinger, Jane Heiden, William Klein, and Kim Komenich. Book prints were made by Amy Whiteside, Tim Burman, and Eddie Dyba; maps by Lori Lietzke.

Carole Kismaric, Michael Kenna, and Gilles Peress have influenced how I understand my own photographs and how I have used them in shaping a story and composing a book. Michael has helped with everything from sequencing images to spotting prints.

The writing and rewriting was the most formidable part, and I'm grateful to those who read different chapters and editions: Steve Gomer, Nan Richardson, Claire Peeps, Raymond Lifchez, Judith Stronach, Jack Schapiro, William Parmer,Steve Heiden, Jeffrey Schneider, Martha Ryan, Ian Timm,

Barbara Smith, and Bruce Buschel. My wife, Katherine Seligman, edited every draft and encouraged me for five years.

My entire family encouraged my work with refugees, particularly my parents, who often provided the financial support that made it possible.

Jan Ralph, at the United Nations, and Jim Breetveld and Peter David, at UNICEF, have been generous with encouragement and support. Without their help my photo work would have been impossible. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) sent me to Sudan, and later Robert DeVecchi graciously allowed me to review the IRC records. Bruce Ostler made it possible for me to return to Sudan, then accompanied me there and encouraged me in pursuing this work.

I wish to thank my co-workers in Sudan. I have high regard for what they brought to their jobs and what it cost them. I regret if this book causes any of them pain. To protect their privacy I have changed the names.

In presenting this account I'm aware it is a highly personal record, not objective history. Others may remember things differently. I record things here based on who I am: someone who is judgmental and critical; impatient and sometimes angry at my own limitations, and, unfortunately, also at the human failings of my colleagues. Despite the problems we faced and the mistakes we made, our relief work was valuable. Such work should be continued.

Finally, I thank the refugees, who will probably never see their pictures or read what an outsider perceived of their tragedy. Perhaps their children or grandchildren will come across this or some other record of 1985, and it will have meaning.

|

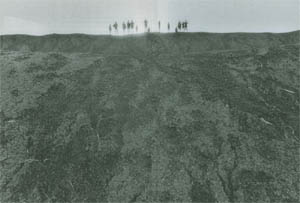

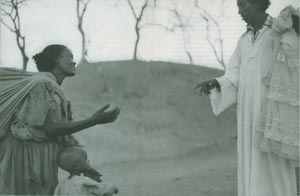

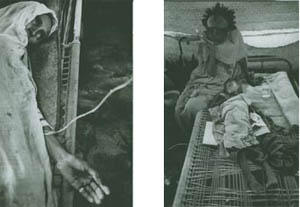

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 20, 1985.

Sarah Barr, the public health nurse,

visits the graveyard

where already 505 people lie buried.

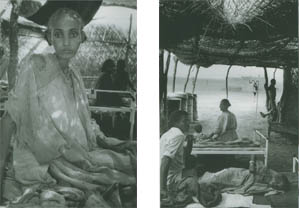

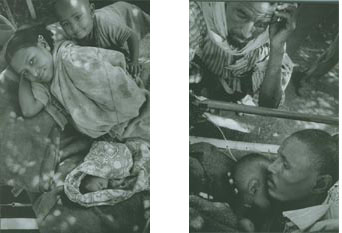

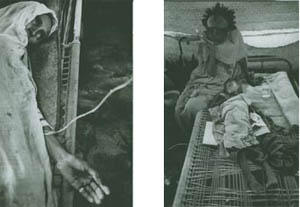

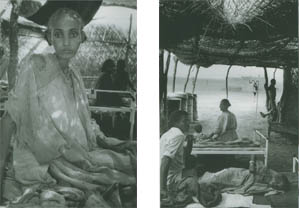

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Woman in the medical clinic suffering from malaria.

Wad Kowli refugee camp, May 1985.

Father and son lie together under a temporary shelter.

Both are ill with malnutrition and TB.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1983.

Mother and child in the Therapeutic Feeding Center.

|

PROLOGUE

A World Away

In the spring of 1985, I left my home in San Francisco to work

in the refugee camps of eastern Sudan. It was an experience that often overwhelmed me and now occupies the space of years in my memory and in my life. I knew I was having an experience with far more in it than I could live as it happened.

I kept a diary, and I compulsively took photographs. The pictures are about refugees, but the story is really about Western relief workers. It is a story about confronting and attempting to remedy a set of circumstances that were far beyond our comprehension or control. It is a story about how we became part of the disaster we were sent to contain.

It took me six months to regain my emotional equilibrium after I left Sudan. It was a year before I could begin serious work on this book, and now, after five years, piles of text and photographs still litter my home.

When I first got back, people would ask me, "How was Africa? What was it like in the Sudan?" I got into the habit of saying, "It was a great place to get a tan and lose weight" and then direct the conversation away. Sometimes when I started to answer truthfully, I could see people get uneasy, frightened by my intensity or by the horrifying things I described. The experience was too complex, with too many euphoric moments and too much pain. I couldn't figure out a simple way to tell it.

After living in an African famine, restaurants were like a fantasy world. Each menu was a paralyzing, overwhelming choice. And I had trouble about food in other ways. It still bothers me to see anything left on a table. When I first got back, I would take home the leftover bread, along with any of the dishes that I, or even a companion, didn't finish. One day I even tried to take home the butter.

For several months I was unable to look at my photos. Then I became obsessed. I went into the darkroom and made print after print, more than a thousand work prints, driven to find something that could not be found in any photograph. Maybe it was a first attempt to control on paper an experience I could not control in any other way. During those hours in the darkroom I used a tape deck to hear books, and I listened to the

entire reading of Winston Churchill's six-volume History Of the Second World War. Then I listened to Daniel Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year, a book of personal observations about a pestilence that happened in 1665.

Ivory Tower in a Jungle

The trip to Sudan was not the first time I'd worked in refugee camps or in Africa. I began by chance. In December 1979, a

friend passed through the emergency room where I worked and asked if I wanted to go to Thailand to help the Cambodian refugees. It had not occurred to me before. I didn't know the difference between Lou Nol and Pol Pot. But I immediately

knew that I wanted to go.

I had been a history major in college and had keenly

followed world events. In the intervening years, in the process of

learning medicine, I had lost touch. I was marking time in the

emergency room, with a vague sense that it was time I started

making a lot of money. The only decision I faced was choosing

a ski cabin for the coming winter. I told in myself that six intense

weeks of charity work in Asia would burn off a dissatisfaction

I could feel but was unable to understand. I also saw the trip

as a chance for free travel, an adventure following which, I

assumed, a career direction would emerge. After several false

starts, in April 1980 I found myself working on a ward at Khao

I Dang refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border.

Then, in the winter of 1981-82, I made another overseas

trip, this time to Somalia. I first thought about working there

while jogging in Golden Gate Park in the rain, trying to heal a failed romance. Africa frightened me. In the midst of planning the trip, I woke up one night from a horrible dream about being in a desolate place and having to sleep in the sand. But my second trip, as expatriate medical director of Boo'co refugee camp, was more fascinating and rewarding than the first.

By the time I thought about a third trip, I had become acting medical director of the emergency room where I worked. I

was encouraged to take the full-time post as director, but was ambivalent. I finally decided not to take the job. In May 1983 I went to Uganda to work on an emergency immunization campaign.

So I arrived in Sudan with some experience. I also arrived with strong opinions. For example, I thought that setting up hospitals in refugee camps was a mistake. I had thought the opposite in 1980, on the Thai-Cambodian border, where another doctor and I managed a seventy-bed hospital ward, in a gravel-floored shack made of thatch, bamboo, and blue plastic sheeting. We worked in a style reminiscent of an American intensive care unit, in the middle of a rice field, with sounds of artillery fire in the distance. It was exciting. With only one day off in a six-week stint, I was too busy to give a thought to what would happen when I, and the rest like me, had to leave. It was "ivory tower" medicine in a jungle, and since there were doctors stepping all over themselves to take care of the Cambodian refugees, I never perceived how incongruous it all was in relation to overall health needs or to what could be afforded and sustained.

In Somalia, in 1981, I was at first shocked to discover that the policymakers in the Somali Refugee Health Unit had forbidden refugee-camp hospitals. They were shrewd leaders and taught us to spend much of our time teaching. All health measures emphasized the importance of sanitation and decent food and water. I learned the fundamental priorities for a refugee-camp doctor. Still, I was not prepared for Sudan.

Civil War and Famine

It's hard to comprehend why, in a world with adequate food, the African famine of 1984-85 occurred. Events in Ethiopia took place against a background of failed development policies for all of sub-Saharan Africa, where Western governments, for their own financial advantage, and World Bank policies encouraged planting cash crops instead of food. In Ethiopia the crowded central highlands of Tigre province suffered years of deforestation and soil erosion. Feudal landlords during decades of Haile Selassie's rule drained surplus wealth with little reinvestment in the rural infrastructure. Then, by 1984, there had been several years of severe drought.

Political conflicts, lunacy, and civil war turned this crisis into immeasurable disaster. By way of engaging proxies to fight cold war battles, the United States and the Soviet Union had heavily armed numerous factions in the Horn of Africa, fueling conflicts in a historically unstable region. In September 1984 the Ethiopian president, Haile Mariam Mengistu, spent an estimated $100 million to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his revolution, while in the countryside his population starved. Well after reliable famine information came out, the Reagan administration remained locked in internal squabbles, reluctant to help a Marxist regime.

Two northern Ethiopian provinces, Tigre and Eritria, were fighting a civil war with the central government, the Dergue of President Mengistu. By late 1984 most of Tigre was controlled by the Tigre Peoples Liberation Forces and their civil/ humanitarian counterpart, the Relief Society of Tigre (REST).

Confronting starvation, peasant farmers in Tigre had two choices about where to seek help: They could look to the government or flee to Sudan. Many went to government-controlled cities to seek famine relief from the Dergue, which used the assistance to their political advantage. Sometimes peasants who were not members of government-sponsored associations were refused food. Relief food was stolen by the government and used to pay their soldiers; in government towns, the peasants risked conscription into the army or forced relocation from their land and resettlement in the south.

The other choice was to seek refuge in Sudan. In the six months between November 1984 and April 1985, REST led approximately 170,000 people in a three-week journey on foot

from Tigre into Sudan. They crossed steep mountains, often walking at night. In daylight, columns of refugees leaving Ethiopia were strafed by government airplanes.

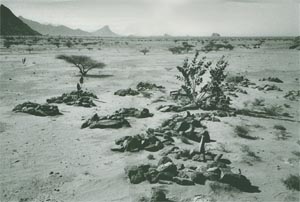

In early November 1984, the first refugees from Tigre crossed the border into Sudan and stopped near a rock formation called Tukulubab, near the city of Kassala. This first famine camp in Sudan became labeled "the death camp" by the world press. Forty thousand people arrived at Tukulubab over the next month.

They were forced to congregate at a desolate spot. Food and water had to be carried in by truck. Bv January, 1985, fuel was so scarce that it was irnpossible to run trucks with enough water for the camp. The daily water ration of two to three liters per person was inadequate for cooking and drinking in a windy climate with more than one-hundred-degree heat. (Refugee experts recommend at least 15 liters per person daily; an average American uses 120.) On certain days near the end, no water at all was delivered.

Evacuation of Tukulubab began in December 1984. Refugees were moved by truck 350 kilometers to the interior, to reception sites that were being set up hastily near the Sudanese village of El Fau. These new camps, Fau 1, 2, and 3, and were located along the Rahad Canal, a muddy, polluted, 100 foot-wide irrigation ditch coming off the Blue Nile.

The migration continued. As December 1984 began, refugees were entering Sudan farther south, near the village of Wad Kowli. This camp on the Atbara River now became the doorway out of Tigre, and by the end of January 1985, Wad Kowli had swelled to more than ninety thousand people. Within a few months the river ran dry, and in March 1985 evacuation of Wad Kowli began.

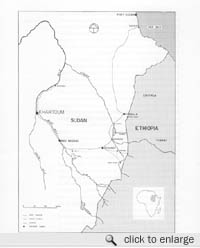

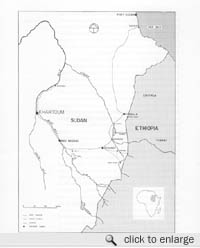

Map of Eastern Sudan. |

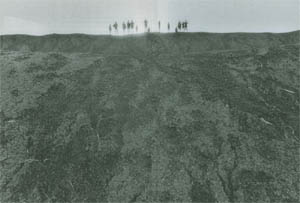

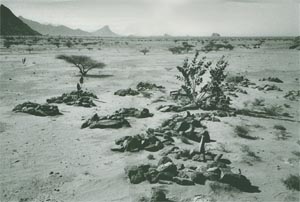

Tukulubab to Fau 3

In January 1985, while the redirected flood of refugees reached Wad Kowli, the brief drama of Tukulubab played its final scene. By this time there were five graveyards, and at the newest site one could count more than two hundred graves. Most of the graves were just heaps of sand without identification, and many were extremely small. Vultures circled overhead.

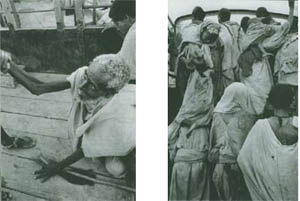

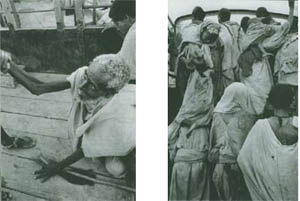

As food, water, and supplies ran out, the pressure to empty Tukulubab increased. Between January 24 and February 8, 1985, the last thirteen thousand people were evacuated to Fau 3. It became a desperate race with disaster. Families were split up. The hospitals, the sick, the dislocated who had been held back were now shipped all at once. Fifty to seventy people were crowded into each closed truck for the seven-hour trip. There was no food or water during the trip.

In every few trucks that arrived at Fau 3, workers for IRC (International Rescue Committee, the New York-based relief group with whom I had enlisted) found a corpse. There is no record of how many died in transit. A small handful of IRC and Sudanese workers frantically tried to prepare the barren site. They did not know how many refugees were coming each night or when they would arrive. One night fifty-four trucks holding thirty-six hundred people arrived between 3:00 and 6:30 A.M., and one truck actually drove into the Rahad Canal. Twins were born in that truck. Miraculously, both survived.

In those first few days at Fau 3, the misery was overwhelming. Tents were not up yet, and the refugees begged for anything to use as shelter against the relentless sun. People even pressed their bodies against the few leafless thorn bushes trying to find shade, and some remained without shelter the entire first week.

Joan Porter was the first doctor in Fau 3. She helped unload the trucks. The hospital was a thatch shelter, and Joan

slept in the hospital on a mat because living quarters for the

expatriates were not yet built. In a single day she recorded thirty-two hospital deaths. Many of the people died before she had a chance to examine them.

A prepackaged "disaster medical kit" was provided. It was designed to last three months in a disaster involving ten thousand people; it was gone in less than three weeks. Then Donna Mosely, the second doctor to arrive, scrounged from the local markets ingredients for homemade oral rehydration fluids for malnourished infants suffering from diarrhea. She complained bitterly that it had been impossible to find the necessary potassium to put in the solution, and she watched several infants die as a result. Later, a nurse arrived from Khartoum and brought generous stocks of packaged oral rehydration salts from the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) that had been sitting in the UNICEF Khartoum warehouse all along. This was typical of the crippling lack of comrnunication that affected everything. Eastern Sudan is a region without telephones. The only way to communicate is by short-wave radio, but radios were prohibited by the Sudanese.

All supplies were hard to obtain, and nothing was easy or could be taken for granted. The sanitarian had to spend most of his time looking for black-market fuel for the water pumps, or else the refugees would be without water. At first the medicines at Fau 1 and 2 were stored outside in the sun, and when Donna organized the pharmacy at Fau 3, every shelf was a minor triumph. The entire camp, a makeshift city for thirteen thousand, had been scraped together in three weeks. Chairs, tables, beds, water barrels, paper, pens, cooking pots-everything-had to be found and put into place. Fuel remained in short supply, and in the beginning there was no vehicle for the new camp. A vehicle came to Fau 3 every two or three days. Otherwise the camp was isolated. The expatriates could not communicate with the outside or leave.

Fau 3, 1985. |

Conflicts within the Camps

Local staff for the IRC health and sanitation programs had to be assembled, a task as difficult as securing supplies, because of typical African tribal conflicts. IRC brought in staff who worked with IRC elsewhere, and this staff was Amharic, mostly English-speaking young men from Addis Ababa who had been in Sudan for several years. They were political refugees. Many had been students and had come to Sudan to avoid military service with the Dergue. Some had been tortured. They hoped for a future in Canada or the Uuited States. They were different from the famine refugees, peasant farmers who intended to return to their highland farms. Tigrayans have generations of mistrust and hatred for the Amharics. They speak different languages.

Antagonisms were further complicated by political problems between IRC and REST. Although the refugees from Tigre were organized and led out of Ethiopia by REST, in Sudan REST was not officially recognized or given power. As the refugees were divided in different camps, the skeleton group of REST leadership sent to Sudan was scattered and undercut. In this sensitive setting, political blunders were made. An uninformed IRC doctor, in an interview for Reuters wire service just after the Fau camps opened, stated that many of the refugees were brought out of Tigre at gunpoint by REST. This fantastic and untrue public statement infuriated REST, an organization dependent on international aid.

Angry conflicts disrupted the medical clinics. REST made accusations: the Amharic workers were not working hard; they were uncaring for the refugees; they were an enemy tribe, Dergue spies. Accusations about REST were made in return. There were confrontations about who should be hired and fired. Threats were reported by numerous Amharic workers. Almost no one in REST spoke English, which complicated getting stories straight and settling disputes.

Crisis Point

Disaster warnings had been ignored. No one was prepared. But in the face of innumerable obstacles, IRC, with a tiny refugee health program established several years before, attempted to extend care to 120,000 additional refugees. By March 1985 IRC had brought forty-one expatriate doctors, nurses, and sanitarians to the camps.

The IRC administrators were as overwhelmed as the medical staff. In February 1985 the program director, Tim White, dispatched a handwritten note to New York headquarters. Everything was in crisis, the other administrator was too sick to work, and he was working as long as he could stretch the day to keep supplies and people moving to the medical staff in the camps. Then Tim contracted both amoebic dysentery and malaria, and he was forced to bed for two weeks.

It was in the midst of this confusion and misery that I arrived in Sudan. Perhaps nothing could have prepared me for what I found.

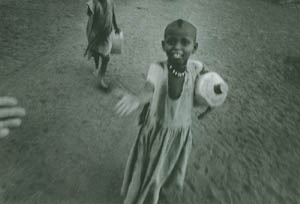

Fau 3 refugee camp |

CHAPTER ONE

SNAKES, SCORPIONS,

AND THE FIRST PLAGUE

Fau 3 Refugee Camp,

March 2- March 25, 1985

March 2, 1985

As we drove closer to Fau 3, the landscape became increasingly barren. There was a single tree in the compound at Fau 1 and no trees at Fau 2..

I felt that we had left Africa and were driving through endless desolation. We followed a dirt track that ran parallel to the Rahad Canal. We couldn't see the canal, only the twenty-foot mound of excavated dirt that ran alongside. On the other side of our car was empty, baked, black cracked dirt that stretched to the horizon.

I can't believe it's only four days since I left New York City. It seems like another lifetime since I met Amy Greer, who is to be my coworker, at the International Departures lounge at JFK Airport. Her huge pile of luggage, with a large stuffed animal perched on top, made me wonder what she expected. She told me about her nursing background in intensive care and cardiac surgery. We talked about work outside the United States. She seemed confident because of experience in Saudi Arabia and in volunteering with a group of plastic surgeons that make weekend trips to Central America. I wonder if the bleak warnings we get every day have affected her expectations like they have mine.

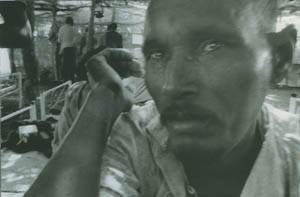

Khartoum Airport felt like Times Square packed into a shed. Khartoum itself was a disappointment compared to the intriguing image brought to mind by the city's name. The city was hot, flat, and dusty, with many unpaved streets. Most of the buildings were low, shabby concrete-block structures. The Nile was low and muddy brown.

In Khartoum the UNICEF representative to the Sudan told me that 4.5 million Sudanese would be starving like the Ethiopians if the May rains again failed. Our talk was cut short by an emergency telex requesting that he provide information for a debate on the famine that was in progress in London, in the British House of Commons.

The short time in Khartoum is already blurred in my mind,

but the five-hour drive from Khartoum to Gedaref was too

ominous to forget.

To pass the time I counted dead animals lying by the side of the road. In less than fifteen minutes, I'd counted twenty camels and cows desiccating in the heat. They were not road kills. The animals were abandoned, because the nomads haven't enough water.

The night we arrived in Gedaref from Khartoum, I sat up late talking with two of the IRC administrators. It was dark except for a kerosene lantern flickering on the table between us. They both seemed painfully exhausted but past the point of bothering, like people so tired that sleep will no longer come. When we sat down it had just gotten dark. Lights were on, but after a few minutes the electricity went off. The fan overhead gradually slowed down and stopped. We sat in the dark for several minutes before anyone got up to find a lantern. The town (and country) is short of fuel, so electricity is erratic. I learned that the program director for IRC is sick and that he has been unable to get out of bed for the last two weeks.

I also learned that Amy Greer and I-the two new recruits-were headed for Fau 3, the refugee camp described as the "pressure cooker" by the administrator of the group of camps (Fau 1, 2, and 3) near the Sudanese village of El Fau. Fau 3 was the last camp formed in the disastrous evacuation of Tukulubab. Only about a month old, it has the sickest population, the worst political problems, and the least organized expatriate staff.

In New York and again in Khartoum, I had been told that I would go to Wad Kowli, on the Ethiopian border, to work with my friend Martha who has been at Wad Kowli for almost a month. I had looked forward to working with Martha. She and I had worked together in a refugee camp in Somalia and during emergency immunization in Uganda.

When the administrator made his announcement about Fau 3, I initially resisted. There were already five medical people, including two doctors, at Fau 3. The public health

nurse, Sarah Barr, had worked in Somalia and is doing fine; but I was told that the two doctors, Joan and Donna, who have no prior refugee camp experience, are not getting along with each other. Worst off are Tom and Candy McDonald, a hushand-wife team of nurse practitioners that arrived three weeks ago. Tom has been sick almost the entire time, and the administrator plans to pick the couple up for a week's vacation in Khartoum when we are dropped off. He thinks they should be sent home. Still, on paper it looks like all the camps are staffed equally thin. I don't want to go somewhere primarily to solve a personality conflict-particularlv not one between two doctors. IRC has no doctor at Wad Kowli.

We sat around in Gedaref for two more days waiting for the medical director. I visited the program director, Tim White, in his bedroom. He's still too weak to get up, almost too weak to talk. I couldn't sleep. I had jet lag, with days and nights mixed up, and it's too hot to sleep in the day. I left New York with the flu, and now I've caught bronchitis. With all the dust I cough constantly, and at night I'm embarrassed that I might be keeping this crowded house awake.

The medical director was due any time, but no one could say exactly when. He has to hitchhike, and the only vehicles on the roads are called Suk lorries, old English Bedford trucks that appear to be left over from World War II. There is a severe shortage of vehicles. There are no phones, and relief agencies are not allowed to have short-wave radios.

The medical director finally arrived late last night, dusty, with a three-day beard, a bandanna around his neck and Walkman headphones. He had just come in from the Fau camps, and he looked like someone that had been camping out for a month. No question the medical need is greatest at Fau 3, with uncontrollable numbers of sick people in the clinics and a terrible shortage of supplies. Also, besides difficulties with the IRC expatriates, there are major problems with the large Ethiopian staff. I was relieved to know from another doctor why I was going to Fau 3, although it sounds horrific. If I can get the situation under control in a month, I still would like to go to Wad Kowli. I told him this.

This morning Amy and I were asked to be ready to leave at 7:00 A.M. Then we sat, like baggage placed by the door. There was no breakfast. At 2:00 P.M. Amy and I started searching the house for food. There was an atmosphere of such rush and crisis that to ask about food seemed petty. We left the IRC house in Gedaref just after 4: 00 P.M.

If there had been an acceptable way to get back in the land rover and drive away from Fau 3 refugee camp, I might have done so the moment we arrived. Nobody even got up to greet us. It felt like we had come, uninvited, into a very private and personal grief. Five pcople-Joan, Donna, Sarah, Tom, and Candy-sat in the IRC compound. They looked on the verge of tears.

I thought back to the night I'd arrived on the Thai-Cambodian border in 1980. There had been a welcome party, followed by enthusiastic orientation. In Somalia, Martha, the team leader, had given new staff a tour explaining day-to-day life in the compound. In Uganda the bishop had hosted a welcome dinner for our emergency immunization team.

Then I looked at the scene in this desolate place called Fau 3. Joan was making corn fritters over an open charcoal fire -one small corn fritter for each person. Opening the single tin of canned corn had evidently been an event. There were only five cans in the cupboard, and they were being hoarded. Comments such as "Oh Joan, this is such a good dinner," "Isn't this wonderful," and "What a treat" were offered as if none of this was really happening, as if this was a slow-motion, melancholy dream.

After dinner the guard, Siam, announced that two people were there to see Sarah. Without explanation she got up and walked off with them in the black night. I learned that they

were two of the translators, Amharics, and that they had been

"threatened" by REST. Sarah returned forty-five minutes later. Several of the workers were going to quit. Then it was Joan's turn to walk off into the night, also into camp, more than a kilometer away, to see if she could "talk things out."

I brought out chocolate from our stopover in Zurich. It was now a liquid mess from the heat. After eating their portion and hardly saying a word, Tom and Candy went off to bed. The rest of us sat up and talked. I wanted to know about the camp. It was obvious that a political crisis was going on. I was filled with uncertainty, but tonight nothing was explained. Sarah, Donna, and Joan brushed my questions aside, and I was depressed and shaken to realize that from my first minute in camp I was being excluded.

I ended the day lying in bed with the most disturbing feelings since I left New York. I have joined an exhausted group under ferocious emotional stress, and they seem reluctant to include newcomers who are outside their circle of pain.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

On my first morning in camp, I walked a quarter of a mile

past rows of dusty brown tents to the clinic. |

March 3

The first thing I noticed this morning is that there are no birds at Fau 3. Birds, acacia thorn trees, vast horizons, harsh sun - these are the African bush. On this continent birds are the spirit of life. In Somalia a family of large doves with strange red eye feathers had nested in a thorn tree hanging over my tent. I had to duck under the branches to get into my tent, and when I left my tent I often stared eye to eye with the doves from four feet away; every morning their cooing had awakened me just before dawn. A ragtag group of noisy, colored birds had been my alarm clock in Uganda where we slept in the servant quarters of an old British colonial estate. They perched on the window and in the tree beside the window just before first light. Twice in Uganda we worked under trees with weaver birds, those brilliant golden yellow birds that hang their strange oval nests upside down, hundreds in a single

tree. We'd pause from immunizing and look up at a tree full of brilliant birds fussing with their nests.

Here the silent sunrise feels like a violation of nature. It leaves an empty space, like the quiet at a funeral, a silence that signifies a break in the normal flow of life. It is another powerful sign of things gone wrong.

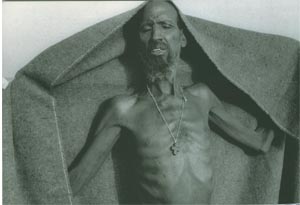

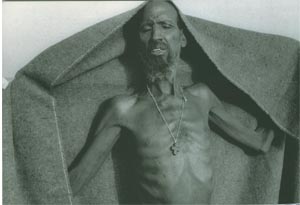

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Hospital patient with

malnutrition and

pneumonia. |

March 4

It's not clear where Amy Greer and I are supposed to fit in or what we should do. I sense unspoken issues of turf despite so much needing to be done. We still haven't talked, and yesterday was not a glorious beginning.

I woke up still sick. By 8:00 A.M. the sun was so hot it felt like my skin would turn brittle and crack like the baked clay dirt. I was thirsty as soon as I woke up. The water filter was clogged with mud. There was no filtered water left, and there was no breakfast.

We walked about a quarter of a mile past rows of dusty brown tents to the clinic. There I saw a crowd of people surrounding the thatch building waiting to be seen. They all looked resigned and exhausted. Inside people sat on straw mats on the ground. Dust was everywhere. Some people, too ill to sit up, lay covered with blankets despite the heat. One skeletally thin 5-year-old girl was racked with spasms of coughing until tears ran down her cheeks. As I watched, her father rubbed her back and tried to soothe her. I realized after one look that she was dying of malnutrition and TB. I learned that there are no medicines to treat TB.

I watched Donna see child after child in the clinic. It was to be a day of tagging along to see how things are done. There was only one translator, so it was impossible to see patients myself. One of the first children needed to be hospitalized. After the translator explained, the mother began crying. It was

an unwanted surprise. In Somalia the refugees had been fatalistic Muslims. No matter what happened, they never cried. If anyone had lost control, it had been us. This tearful outburst shattered a barrier that I had unconsciously remembered. It brought me uncomfortably close.

Then Donna examined a 10-year-old boy whom she and Joan had treated without success. The child had a swelling on the shaft of his penis. There appeared to be a small tract draining pus. I thought it was an abscess that needed to be opened and drained, and after giving an anesthetic injection I made a small incision. No pus came out. It was my first patient, and all I had done was make things worse. I dressed the wound and got some new medicine, which I gave to the father. I told him to bring his son back, and I would try another medicine if this failed. With solemn formality the father and his boy both shook my hand. Their gratitude gave me a hollow, sick feeling after the mistake I had just made.

Things went no better in the seventy-bed hospital, where many of the patients will obviously die. For a while I followed Joan in her distraught pilgrimage from one bed to the next. Then I found someone who spoke enough English for me to work independently. The beds are arranged in five long rows. I started at the other end of the ward, at the first bed of row E. At the last bed in row E, I cried.

A 25-year-old woman and her 2-year-old daughter shared the bed. The mother has been treated with all our available antibiotics. She is feverish and weak. Nothing has helped. She has been coughing up blood for the past four months and is obviously dying of tuberculosis. She is too weak to take care of her child, and the child is fed by the sick woman in the next bed. The child is malnourished and covered with flies. We have no drugs to treat the woman's tuberculosis, and her cough is highly infectious. To protect the other patients, we should send her out. There is nothing more we can do for her, and we need the bed for other sick people. But the translator

tells me she does not have a tent and that she has been separated from her husband and village. The translator says they are at Wad Kowli, but it is impossible to communicate or travel between here and there. If she is sent out, no one will care for her child, and the child will die.

I stood there overwhelmed with responsibility to do something. Any action I could take seemed monstrously inhumane. To do nothing seemed like avoiding my job and seemed equally unfair.

(I did nothing but told myself I would speak to Joan. Other problems rapidly pushed this woman out of my mind. Several days later I went to find her. She had died. I searched but never found the child.)

Fau 3, March 1985.

Another child has died from fever, diarrhea and malnutrition. |

Amy's first day went no better. Tom and Candy, for at least the coming week, are gone. The nutritionist who runs the Therapeutic Feeding Center, also left for a few days, so the feeding center was Amy's logical place.

Amy Greer was faced with several hundred crying, coughing, fly-covered, starving kids packed in a hot thatch structure. The children sit on mats on the ground with a parent or older sibling, and the bodies are so crowded that it's difficult to walk across the enclosure without stepping on a baby. Many have diarrhea, and there is no place to take them. The place smells. The temperature outside is 110 degrees. Inside this cramped shelter with so many bodies and no breeze, it feels smothering and overwhelming. The sounds of feeble crying and coughing come from every direction.

Malnutrition is diagnosed by measuring the child's height and weight. If a child weighs less than 85 percent of the predicted weight for a measured height, that child is, technically, malnourished. Here children are not counted in that category unless they are under 80 percent, and by that criteria between

one-third and one-half of the children in this camp are malnourished. If they are under 70 percent, they are "severely malnourished" and are sent all day to the Therapeutic Feeding

Center, which serves six high-calorie meals over the course

of the day.

Most of the children Amy found in the feeding center were under 5 years old. Children that age are the most vulnerable to malnutrition. If the mother is alive, a child is usually well fed until leaving the mother's breast, at about six months of age. Then follows the period of greatest jeopardy. The child is growing most rapidly, has the greatest nutritional and metabolic needs, but is not yet able to feed itself. The child will compete unsuccessfully with other hungry mouths. And the child has not yet had the common illnesses such as measles or whooping cough, which exacerbate malnutrition. Finally, it's a cruel fact that little children are the most expendable. Older children can work, and if the parents starve they know that all of their children risk death.

It takes no measuring to appreciate this situation. I've seen children 10 or 15 years old with severe malnutrition, an indication of extremely bad conditions. I've also seen frightening cases. Fifty-five children in this camp are less than 60 percent of their predicted weight. They are pitiful skeletons, sometimes too weak to cry, and it is impossible for me to look at them and not remember pictures of Dachau or Buchenwald.

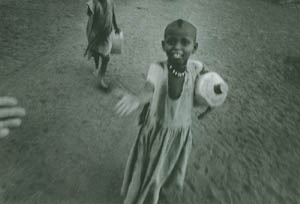

I left Amy Greer in the feeding center at 8:00 a.m. She had a tough time figuring out how to begin. When I went back at the end of the day, the place looked like a Fellini circus. Most of these skeletal children had mouths painted purple, or irregular blotches of purple on their shaved heads. They looked like pathetic clowns.

Amy had started by treating every child that had scalp ringworm, or thrush (yeast infection of the mouth), with Gentian Violet. She did something graphically visible to defy feeling overwhelmed.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Joan Porter has had a fever on and off for a week, and today we noticed that her eyes are yellow. She has hepatitis and will go home.

|

March 5

Our guard, Siam, and our cook, Eiosis, refugees in their late forties, carry themselves with a sad paternal air. Neither speaks a word of English, but they both speak a little Italian, a relic of Ethiopia's colonial past. Siam will occasionally try a few words in Italian out of frustration when we don't understand something. They are not subservient, and our relationship is different from any at home. It is almost as if Siam regards us as children whose care has been entrusted to him, children who think they are capable of looking after themselves but really aren't. He is responsible for seeing that we come to no harm, and he takes a great interest in us. Eiosis is gentle, speaks quietly, and covers her mouth in shyness whenever she smiles. She arrives in the morning with a black shawl wrapped around her head that she carefully takes off and folds. She also takes off her shoes, and she puts them away with the shawl. In the evening before she leaves she puts her shoes and shawl back on.

Today was food distribution day in camp, distributed to each head of family. Each person got a ration that is expected to last fifteen days:

3 packages spaghetti

900 grams lentils 3 kilograms flour

150 grams salt

150 grams chile peppers

oil (a few cups)

charcoal for cooking fires

Sarah Barr tells me that up to now each ration has been

different depending, she thinks, on which country was donor.

What is the same, she says, is that before the end of each

period most people are without food.

Sarah is in charge of public health. Her work takes her

inside the tents, where the rest of us rarely go. Sarah is doing

exactly what needs to be done. She is training a group of

thirty in primary health care: recognition and treatment of simple common problems, particularly diarrhea and dehydration. Her workers go tent to tent distributing soap and razors when these items are available. They record births and deaths. They try to find sick people. Only about half of the malnourished children show up at the Therapeutic Feeding Center, and Sarah's group tries to find the children who fail to come. They distribute shrouds. They report to Sarah when tents are blown over or ripped by the wind, and Sarah gives the list of destroyed tents to Abdulmonim, the project manager (Sudanese camp director), who sends help to repitch them.

They also report to Sarah things that she can do nothing about-like the fifty-four old people. Sarah carries this list around with her and brings it out for discussion at every camp meeting: "What are we going to do about the fifty-four old people who are sick and separated from their families and villages and lying in tents unable to care for themselves?" They are victims of the social disruption of the move from Tigre and then from Tukulubab. REST has said they will make an old-age home, and Sarah takes out this list of neglected people, whom she says will die before anything gets done.

Today we were visited by a medical school dean from the board of directors of IRC. He's here to evaluate programs in Sudan, and he obviously cares about us and about helping the refugees. He worked on the Thai-Cambodian border and apparently sees things based on that experience. In Thailand resources were plentiful, and most of our efforts were spent on curative medical care. Lessons from Thailand are a curse here, and his last question gave it all away. "Have you coded anyone yet?" he asked, meaning had we tried cardiac resuscitation on someone who died. "Coding" someone is a symbol of curative medicine at any cost. It is as medically appropriate to this camp as diet pills. Joan said that she had.

I gave our visitor a small package to drop off at UNICEF

in Khartoum for the diplomatic pouch to New York. I have

photographed for UNICEF in Somalia and Uganda. It was the

first six rolls of film of the camp-my first impressions-plus a letter to the UNICEF photo chief, Jim Breetveld, written by flashlight at 11:00 P.M. last night, when I was exhausted and overwhelmed by my first days in this place. This horror must be seen, I thought over and over to myself as I fought sleep and wrote Breetveld. When I handed him the film, I explained that UNICEF was waiting for information and would make good use of fresh news from Sudan. If I get only one good picture, please let it be now when it might do some good.

(The film and letter were lost, which I learned three months later when I got back to New York.)

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

A child recovering from measles.

|

March 6

The hospital is not working, despite the best intentions. We are spending too much time trying to cure people near death, at the expense of preventing illness. Right now we face epidemic malnutrition, polluted water, no immunization, inadequate shelter, no sanitation, and a disrupted social fabric. If we cure someone's illness in the hospital, he will only get sick again because we send him out to starve, freeze at night, and drink polluted water. If basic human necessities were provided, we probably wouldn't need a hospital. Hospitals are an overwhelming political symbol of help, but I see them as a trap for our good intentions and a symbol that leaders and policymakers don't understand the priorities.

Too many Western doctors fight the wrong battles. Like Joan, who leaves for the hospital about six each morning and returns after dark every night, usually close to 9:00 P.M. She spends her entire day in the hospital making rounds, examining and reexamining patients, many of whom are certain to die. She starts intravenous lines, but under current circumstances these seem largely impractical. We have few or no

satisfactory needles, and we are often out of tape. In the ten or fifteen minutes while an intravenous line is being started, every worker in the ward stops work and crowds around to watch. Attention is diverted from more important but unexciting tasks, like feeding and giving oral rehydration. These hard and messy tasks are often neglected. Meanwhile, most of the intravenous lines do not last an hour. In a furious doctor's scrawl on tattered scraps of paper, Joan writes daily notes on each patient: "medical records" that no one will ever read. In most cases we will never prove or disprove the diagnosis, because we lack the necessary tests, and much of the illness we will never treat because we lack the means.

We spent at least an hour yesterday morning looking for tape and tearing up index cards to mark the beds of several new patients. We made squares for patients needing halfstrength milk and circles for patients needing full-strength milk. But at the same time, the entire hospital receives inadequate food.

Still worse, almost three-quarters of the deaths so far have occurred outside the hospital, unreached and largely ignored by our system of health care. How many of those deaths out in the camp were children with malnutrition and simple diarrhea, children who could have been saved? Hospital medicine is not the answer if we hope to solve the health problems of this camp. It doesn't matter that we're doing things for admirable reasons, and it doesn't matter how hard we try. It's like throwing a tennis ball straight up in the air with all your strength, trying to hit the moon.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Banks of the Rahad Canal on the west edge of camp.

|

March 7

The outpatient clinic is a long thatch hut divided into five areas. It faces a large, thatched sun shelter called a recuba, where people wait. About 250 to 300 people come to the clinic each day. Ten or twenty people sleep under the recuba overnight, hoping for a favorable place in line for the next day.

The first area is registration and screening. Several refugees (with no medical background except for Sarah's cram

course) prescribe treatment for most complaints by simple formula. They have not been taught how to examine a patient or inquire about symptoms in any depth. A person who complains of fever and chills is prescribed treatment for malaria, chloroquine for three days. A person with cough and fever gets an antibiotic for pneumonia. Cough without fever is a cold; no antibiotics. The list of diseases and treatments is short but elastic. People who can walk and don't look too sick receive superficial attention and are sent away.

Sicker patients go to the next room and see one of the two trained Ethiopian examiners, Donna, or me. The third area is for oral rehydration, a separate room where we send all patients with dehydration and diarrhea. Diarrhea is a leading cause of death, and if dehydration is prevented with the proper amounts of fluids mixed with sugar and salts, most of the deaths can be prevented. Then comes the treatment room (for injections), the pharmacy, and two rooms for teaching and public health.

The clinic goes slowly, because we are short of translators. There are only five people in the entire camp who are fluent in both Tigrinyan and English. One of them translates for Joan in the hospital, and the other four have important jobs and can not be spared just to translate. So far I've tried using a translator for whom I actually have to pantomime. I've sometimes used two translators-the first translates from English into Amharic, and the second translates from Amharic into Tigrinyan. Then the answer from the patient has to come back by the same route. The answers often make no sense. The translators pretend to understand the questions and answers, because they fear exposing how little of the language they actually know. The translator jobs are prized. It's painful to see how hard they try while lacking the essential skill, and it's frustrating to constantly wait for information that usually doesn't help.

The most common disease in the clinic has been dysen-

tery, bloody diarrhea, because we ran out of chlorine for the

water supply. Somebody sent us alum by mistake, which we used for about two weeks. Each day the sanitation assistant tested the chlorine level in the drinking water and announced that the water was "OK."

Alum is used to precipitate the gross impurities in the water and cause it to settle to the bottom of the tank. Alum is helpful if the water is filtered or drawn off the top of the tank. The tanks we have draw from the bottom, from where all the polluted sludge ends up.

This foul water has given between one-quarter and one third of the camp bloody diarrhea, and it has probably killed some of the malnourished children. The pharmacy shelves are rapidly emptying of Septra, tetracycline, ampicillin, and chloramphenicol-antibiotics to treat diarrhea. All this medicine has little effect, because the refugees continue drinking the polluted unchlorinated water. They can't boil it, because we are short of fuel. There is no wood on the site. Some of them get up at 3:00 or 4:00 A.M. to walk several hours looking for wood, but they use it to improve their living compound, making windbreaks and better shelter. Besides, no one wants to make extra fires. It's 110 degrees outside.

What this camp obviously needs more than antibiotics, hospitals, or doctors are a few cheap drums of chlorine.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

The pharmacy..

|

March 8

I went in to the clinic at 7:00 A.M., and about an hour later someone ran in shouting Amy's name and motioning me to follow. In the feeding center I found Amy standing over a 4-year-old girl in a coma taking what looked like her last breaths. The child was skeletal. The final event in these cases will sometimes be dehydration and a sharp decline in the blood sugar. We took a bottle of intravenous fluid containing dextrose, and I showed Amy where to insert the needle directly into the child's abdomen. Fluid ran in for two or three

minutes, and to our amazement the child revived. Her eyes

opened, and, very feebly at first, she began to move her arms

and then to cry.

I wrote a note for Joan telling what happened. We had not noticed the mother at first. We found her waiting in silence only a few feet away, sitting on the ground with her face covered. Amy and I felt an excited euphoria. We had saved a life. But in spite of our success, the mother's eyes showed only pain and loss, and her face still glistened with tears. We found a translator and explained for her to carry her daughter to the hospital with the note for Joan. (In the hospital the child lived one more day.)

I returned to the clinic and saw patients until 2:00 P.M. I tried working without a translator. Using a list of about fifty Tigrinyan words prepared with several of the workers late yesterday afternoon over a few cups of tea, my questions were limited to fever, cough, and diarrhea.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

A child blind from lack of vitamin A.

|

I saw many patients with unusual illnesses often caused by lack of vitamins. Many people have unexplained swelling (edema) of their legs or abdomen, or of the scrotum in men. This is probably a form of wet beriberi, caused by thiamine deficiency. Another form of thiamine deficiency, called dry beriberi, affects the nerves. There are many people who complain of burning or pain in their hand or feet, and some people have trouble with balance, walk with a very wide gait or can't walk at all. Thiamine deficiency can also cause altered behavior, even psychosis. There are people in camp like that too, but it's impossible to be certain of the cause. Our vitamin tablets don't have adequate thiamine to treat these patients.

Pellagra, caused by niacin deficiency, is in this camp as well. The word comes from Italian, meaning "rough skin." We find patches of what looks like crocodile skin on the forearm or shin, in areas exposed to the sun. I had seen one case on the Cambodian border in 1980. Here the disease is common. Lack of niacin also causes diarrhea and dementia, but

in Fau 3 there are so many other reasons for those problems

that it's impossible to tell what the cause is for every symptom.

We wrack our brains trying to sort out these bizarre vitamin problems, and we search through the medical books to figure out the correct treatment. Then we rummage through the pharmacy trying to find the right medicines. Often the tablets are the wrong dose, or we need injection and only have pills, or our supply is already exhausted. We send urgent messages for more medicines. What a costly, dismal substitute for decent food.

I walked back to our compound in the middle of the afternoon, dehydrated, exhausted, spirits numb. I drank a full liter of water, had a bucket shower, and then drank more water. I put on a wet shirt and wet shorts, and sat in my tukul hoping to cool off. The water evaporating from my clothing made me feel cool and comfortable for only fifteen minutes. Then my shirt and shorts were bone dry.

Everyone who was back in the compound gradually wandered into my tukul. There are now three hammocks strung up, and with my cot it's a place we can gather. In Somalia we worked out camp problems while lying around in the hammocks at night. Perhaps setting this up will help us organize ourselves better as a team. We talked about improving the way we feed the hospital patients. Several people alluded to the lack of understanding or agreement about our priorities and who is responsible for what tasks.

March 9

Amy Greer was evacuated from camp today, after lying in her tukul off and on for several days. She is being taken back to Gedaref. She worked less than a week before getting sick. I think she caught amoebic dysentery from our water.

Her illness makes me think about the difficulty I'm having trying to get settled. I've gradually realized that there is no daily routine. There's no administrator or logistics person in this camp, and none of the doctors or nurses has taken the time or had the energy to organize how we expatriates live, eat, or will maintain our health. It goes deeper than that, as if taking decent care of ourselves would be some form of violation in the face of so much misery that we are failing to relieve.

The tukuls, the round straw huts we live in, are dusty beyond belief. Insects crawl through the straw walls and drop from the ceiling. At night the wind blows through, and during the day the tukuls give no insulation from the heat. Even the poorest Sudanese mud up the walls of their tukuls. There is no field shower. To wash we stand on a handful of straw in the mud and pour a bucketful of water over ourselves, cup by cup. Eiosis cooks dinner, but no one tells her what to make. There is no organized breakfast, not even a fire started and water boiled. Eiosis would come in early and help, but Joan says "I can't bear to have those people around so early in the morning. I just want peace and quiet." There is an emotional tone implying that eating breakfast is an indulgence. Joan does not stop or come back to the compound for lunch, and no lunch is prepared. No one has taken the effort to arrange it, work out a menu, or find a translator to arrange things with Eiosis.

Joan, Donna, Sarah, Tom, and Candy have been working themselves to exhaustion the last few weeks. Everyone but Candy has been sick. Joan was here first and set a standard of physical exertion, suffering, and self-denial that no one can maintain for long. The rest of the group, punchy with fatigue and emotionally overwhelmed, stagger on this path behind her. Our living circumstances and medical priorities seem intertwined.

At breakfast today I again asked that Joan, Donna, and I have a talk. I said we needed to work on priorities and organization of the team. Joan said she was too busy for meetings and too tired at the end of the day, and then looked away. I finally

insisted, and the meeting was set for 6:00 A.M. tomorrow. Joan

walked off to camp. Donna followed me into my tukul and asked me not to interfere with Joan's work, to let her continue doing what she wants. (The meeting never happened.)

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Malnourished child in the hospital.

|

March 10

Journalists and politicians steadily come through camp, because we are near the only paved road going east, toward the Ethiopian border and other camps. Most of the visitors are glassy-eyed from jet lag and heat, and they are horrified that babies are indeed starving. Today there was someone different, a reporter from the Los Angeles Times, familiar with the scene and unsurprised at the starvation and misery. In the form of questions, he proposed a cold-blooded and cynical view: Who ever heard of Tigre before these starving people arrived in Sudan? Now their story, pictures of their starving babies, and calls for support are front-page news around the world. What would have happened to the TPLF in the civil war if all the peasants went to government relief centers instead of Sudan? Underneath it all, what mixture of hopes and motives really set this dramatic catastrophe in motion?

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Hospital.

|

March 11

4:00 A.M.

It took me just over a week to get sick. I have cramps and diarrhea. Since midnight it's been impossible to sleep. One month here will be my physical limit, and I will be lucky if I last that long.

AFTERNOON

In between visits to the latrine, I've been trying to remember what we did in Somalia four years ago. I've brought the kitchen table into my tukul to use as a desk. I sit here, with a

pencil in one hand and Pepto-Bismol in the other. I'm drafting a set of simple descriptions of the most common medical

problems with simple instructions on how to treat.

In this chaos, overwhelming needs send us in every direction. With no guidelines we get lost. On a deeper level, there are confused needs and motives in all of us, and there is always an unspoken confusion between doing what is needed and doing this work as an emblem of our own humanity. It's too tempting to simply work each day to the point of exhaustion and not take a critical look.

As we work we should he training ourselves out of a job, making the refugees independent as rapidly as possible. Without a written document it's hard to teach or standardize care, or to keep priorities in focus. I've been writing for several days, and Donna and I stay up together each night revising the draft. What a pity the medical care guidelines developed in Somalia four years ago have not been provided.

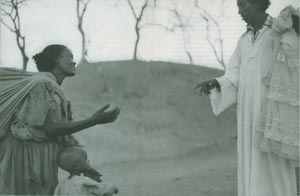

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

A woman learns that

her husband has died

suddenly of meningitis.

|

March 12

Joan is off in Wad Medani for a few days' rest, and Tom and Candy are back from Khartoum. They have decided to stay. In Joan's absence I made rounds in the hospital.

I admitted to the hospital a 30-year-old man who had a high fever and was in a coma. I tried to do a spinal tap to see if he had meningitis but failed because I only had a needle we use for injections. The needle was too short. I couldn't reach the spinal canal. So I treated him for both meningitis and cerebral malaria at the same time. He looked near death, and both diseases were possibilities. He died four hours later. The women in the family who had been crowded around the bed began crying and wailing. They left the ward waving their arms in the air. The men tied his arms across his chest, closed his mouth, and wrapped him in a thin white shroud. The funeral was held just outside the ward. Then they carried

the body to the graveyard, which is about 150 yards from the

hospital, straight out in the open field. The men were in a group carrying my patient, and the women followed in a separate group about 10 yards behind. I went outside and watched. I took a few pictures and felt dizzy in the 115-degree heat.

Tonight we had a pot luck "dinner party" at Fau 2 for the expatriates of Fau 1, 2, and 3. The people from Fau 1 did not show up, and we heard that two of them are sick. We sat outside in the dark on two creaking rope beds. The lantern went out, and no one cared enough to get up and find more fuel. Everyone looked tired and depressed.

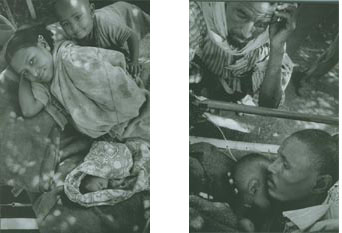

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

Therapeutic Feeding Center.

|

March 13

It's near the end of my second week here, and finally I have some sense of productivity. Donna worked on organizing a better system of feeding the patients in the hospital, and I worked on the clinic. We roped off lines in the clinic and put up signs. Nishtey (children) get a special line so they will be seen first.

Sarah is out of camp, so I gave the daily lecture to the public health workers and organized a rotation system for them to work in the clinic as training.

Then I collected the new list of tents blown down to give to Abdulmonim. There were only a few tents on the list. On days like today that are still and hot, miniature tornadoes, called “dust devils,” spin through camp. If the tent is fastened tightly, it rips apart; otherwise it just blows away.

In the afternoon I went to the feeding center. I examined about twenty children, but I'm most concerned about Halima Mariam, a frail 4-year-old girl who is cared for by her 9-year old sister. She is again refusing to eat.

I saw her in the clinic last week and admitted her to the hospital. Then she had diarrhea, was losing weight, and refusing to eat. She is one of the children who is less than 60 percent of her predicted weight. In the hospital Joan put a

feeding tube into her stomach, and force-fed her for several days. I saw Halima in the hospital with the tube coming out of her nose. It was taped to her forehead with black electrician's tape, the only kind we have left.

Then I saw her three days ago, and she looked bright and was eating. Halima was released from the hospital, and her sister started bringing her back here to the feeding center. It looked like Joan's stubborn determination had saved this small girl.

Now Halima has a cough. Maybe she has pneumonia, but I doubt it because her lungs sounded clear. She may just have bronchitis, an infection in her upper airways. Without an X ray we can't really know.

These severely malnourished children are fussy eaters. They seem to lose interest in food. A sore mouth, an ear infection, or any other trivial illness, and they refuse to eat. To save them requires persistence and hard work. You have to reacquaint their shattered bodies with the will to live. Halima has no reserve. She can't afford to lose any more weight. She has to go back into the hospital and again be force-fed with a tube.

Halima in the Therapeutic Feeding

Center, refusing food offered by her sister.

|

These children are so fragile. They are the sickest group in the camp. A doctor from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) did a survey at Fau 2 last month and found that in only two weeks, 72 children died, out of 418 registered for therapeutic feeding. Parents bring the children to the clinic for an injection, but don't bring them to the feeding center. It's a fight to try and feed them all day long. The parents don't realize that injections and pills are useless if the children don't eat. Some of the children are so weak they need to be carried, and the parents aren't well enough to do this, or they live too far away. The children get quiet and apathetic and are easily ignored. We are not doing an adequate job with the malnourished kids: Less than half of the total number of severely malnourished children in the camp regularly come to therapeutic feeding.

In the clinic I sit with four refugees in training. No matter

what the complaint, I make them check each child's upper arm

or thigh to look for wasting. The clinic has been rearranged so mothers and children sit inside on long wooden benches where they can see what is going on. I say over and over: Malnutrition is the worst disease, food is the best medicine. I've learned the Tigrinyan words a bila eyo (feed him), which I repeat to mothers holding the thin limbs of their infants. Sometimes I pick up a child and show the other mothers. I pantomime how strong the child will get if he eats, and the crowd of children and mothers laugh. I'm oblivious to how ridiculous my acting may appear. I want them to remember what I say.

Late at night Donna and I were still up working on the medical care guidelines, when a truck rolled in with twenty-nine sacks of CSM (corn-soy-milk powder) for the feeding center. One by one, everybody already in bed came out to see what was going on. We discovered that the truck also had another thirty-two huge cases containing Ritz crackers, courtesy of the government of Japan. I wonder who decided we need so many Ritz crackers. For a few minutes we made tired cynical jokes about evening cocktail parties for the refugees and about English butlers with silver trays serving the children their malnutrition porridge on Ritz crackers.

Fau 3 refugee camp, March 1985.

A child in the Therapeutic Feeding Center is gaining weight.

|

March 14

Everyone is losing weight. Sarah, Tom, and Joan blame their poor appetites on the heat, but there are probably psychological reasons as well that come from the constant contact with so much starvation and misery. Our food is so limited that I suspect last night's Ritz crackers are going to become a major item.

In the morning, Eiosis, our cook, sits down with a pan of dried lentil beans and patiently begins flipping them up in the air, again and again, each time uncovering another twig or

pebble. She is usually at work when I leave for clinic in the

morning, and sometimes still at work flipping the lentil beans

when I return to the compound for lunch. Eventually she boils them or boils potatoes as an alternative. The afternoon is spent making a small mound of finely chopped onion, red pepper, and garlic, which is fried in oil and put on top of the boiled vegetable as spice. This has been dinner almost every night: boiled lentils or boiled potatoes.

In the last few nights I've started to cook, and Eiosis and I cook together. She regards my combinations (like frying eggplant and tomatoes and garlic and pepper together-and then putting it on top of spaghetti) as crazy. She laughs or shakes her head or waves her arms when she thinks I'm going completely beyond the bounds. We have no common language. When I discovered that she speaks a little Italian, I tried to speak to her in Spanish, hoping we would hit an occasional mutually understandable word. The effort was useless, and we both soon gave up. Now we just talk back and forth without regard, Eiosis in Tigrinyan and I in English.

March 15

Among all the sick and malnourished in the clinic today were two lively healthy kids who had stuck beans in their ears while playing. Shimelesh, one of the examiners, tried to irrigate them out without success. No head mirror. No bayonet forceps. I tried to hook one of the beans with a bent needle without luck. When I went back in the afternoon I brought superglue and put some on the tip of a wooden Q-tip but it wouldn't stick to the bean. So much for that advertisement about lifting a piano. I couldn't think of anything else to do, so I told the parents to bring them back in a week. (A week later the beans had dried out and shrunk, and I was able to remove them with our clumsy forceps.)

After I got back to the compound, someone brought a note

from Donna asking me to come help with a kid who seemed

to have a broken arm. While walking back I was hoping that the kid had dislocated his shoulder and not broken his arm. I can diagnose a shoulder dislocation without X rays, and it's easy to put back in place. When I got to the ward I found the kid heavily drugged, almost in a coma. Donna had meant for the kid to have a teaspoon (5 ml.) of sedative by mouth. What he had received was the same volume by injection, which is ten times as powerful as the oral dose. Similar errors probably happen every day. The staff is untrained, overburdened, does not speak English, and in these circumstances it is impossible for us to adequately supervise and explain.

The child's arm was not deformed, but the middle of it was very tender and there was a lot of swelling. I put on a plaster splint and asked that the child stay on the ward for the next two days so we could watch him. (The next day when I came by to check he was gone. I never saw or heard about him again.)

After dinner Donna and I sat up working on the medical care guidelines by the light of a kerosene lantern. When she reached for her backpack, which she had set on the ground in the corner, she got stung by a scorpion. Squeezing her right hand she screamed in pain. I injected her finger with Xylocaine for the pain.

March 16

For the last two days we have been out of chloroquine, ampicillin, Flagyl, tetracycline, Septra, and penicillin. We can give only oral rehydration fluids to patients with dysentery. With only this treatment some of the weaker children may not survive. The director of the pharmacy is a political refugee from another camp, Tenedba. He is a very serious, conscientious man, and he speaks English in a dignified formal manner.

He has been in Sudan for five years and worked for IRC as a

pharmacist at Tenedba.

He and I have a routine. "Doctor. .." he begins haltingly, "I must have a moment of your time to bring to your attention a most urgent matter." He then presents me with the list of needed supplies. As I glance down the list, he gravely reads it out loud, usually with the same comment -"finished"-after each item. "Penicillin: finished ... sticking plaster: finished ... Septra liquid: finished ... Septra tablets: finished." I thank him for bringing the needs to my attention and tell him I will do what I can. There is actually little that I can do. In between patients Donna keeps track of supplies, which is equivalent to supervising a large hospital pharmacy. She sends in the drug requests to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for shipments that are delivered every two weeks, but it doesn't seem to matter what we request. They send us what is available, dividing it up fairly between all the different camps. No one gets all that is needed. If we are particularly desperate we can go to Fau 2, or Fau 1 and try to borrow, but the most commonly used medicines are in short supply everywhere.

Yesterday in the pharmacy Donna found small amounts of everything being saved. Above her rising incredulous voice, I heard our dignified pharmacist vainly protesting that those medications were being saved "just in case." "In case of what?" asked Donna. "But ... Doctor Donna ... in case of an emergency!"

March 17

There's an epidemic of scurvy in Fau 3. It's been unrecognized, in front of our eyes. Several days ago we talked about the many patients with strange arthritis, patients crippled with painful swollen knees or painful ankles. Donna tried treating

them with aspirin and noticed it didn't seem to work. Wasn't

it a pity, she said, that we didn't have stronger arthritis medicines that are available in the United States. This morning three patients, almost back to back, came into the clinic with nosebleeds (a possible sign of scurvy). All three had swollen bleeding gums (a classic sign of scurvy). One of the patients also had knee pain. Finally, the diagnosis was apparent.

Scurvy is caused by lack of vitamin C and leads to fragility of the tiniest blood vessels. The patients tend to bleed, but often in a way that is hidden. This strange arthritis that we have been misdiagnosing is caused by bleeding about the weight-bearing joints, bleeding that occurs under the lining of the bones. Aspirin increases bleeding, only making the problem worse.

We checked our supply of vitamin C in the pharmacy and found that we have enough to distribute to the entire camp. The public health workers will give every refugee a 200 mg. pill of vitamin C twice a week, and we will send an urgent message to the central pharmacy for more. (With mass distribution of vitamin C scurvy disappeared from Fau 3. Workers in Fau 2 were not convinced that all this arthritis was from scurvy, and they did not mass distribute in their camp for several more weeks, until the scurvy in Fau 2 got even worse.)

On the way home I stopped for a visit at the REST compound. Their tent has no ventilation, and after two cups of tea I was dripping with sweat. I explained that I will start giving medical classes in the afternoons and hope to get treatment guidelines translated into Tigrinyan. Araya, one of the REST leaders, works with me in the clinic. He's in his early twenties, handsome and forceful, with a natural sense of authority. Arriving at the clinic before anyone else each morning, he stays

without a break. I asked him what he thought about all of

us starting clinic an hour earlier, at 6:30 A.M., because of the heat. He agrees it will be a good idea, and tomorrow we will change.

Most of the time we just sat there together drinking tea and

not talking, because we have very few words in common. I will keep visiting so they get to know me. They need confidence that IRC is interested in working with them.

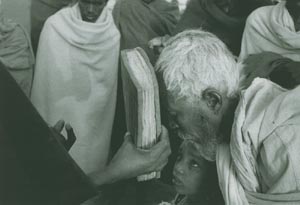

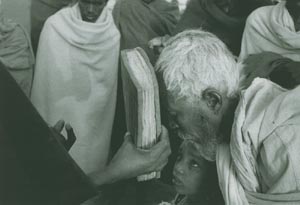

Fau 3 refugee camp,

March 18, 1985. Godamu

Geberselassie died in the

clinic before I even had a

chance to figure out how to

spell his name.

|

March 18

A dusty wind blew all night. I slept poorly and had a nightmare about snakes. The guards have killed two of them this week. They were brown, about two feet long, with a triangular head: some type of poisonous vipers, either night adders or baby puff adders. Then last evening as we sat in the kitchen enclosure, another identical snake crawled between our chairs.

Work was long and hectic. An elderly man, Godamu Geberselassie, was carried into the clinic on a stretcher by two men. I looked down at my paper to write his name, and when I looked up they were covering him with a blanket. He died before I even had a chance to figure out how to spell his name. Sick and separated from his family and village in the move from Tukulubab, he had lain uncared for in a tent. (Later, I learned that he was one of the fifty-four old people on Sarah Barr's list.)

Shimelesh, one of our examiners, is now out sick after asking for vacation for the last two days. At work today he started vomiting and collapsed on the ground with a shaking chill. He has malaria. Joan is also sick. When I get up at night I hear her cough. Last night at 1:00 A.M. I gave her some medicine for the cough so she could get back to sleep. She has had a fever off and on, and she has been ignoring simple things like watching what water she drinks and washing her hands before she eats. Tom again has dysentery.

Last night Sarah Barr shaved her head. She had to convince us that she really wanted to do it before we would help. We all took turns, first cutting her hair short with my bandage scissors, and then shaving her scalp with a razor blade and

soap. She joked and said that she had always wanted to do it.

She said she "needed a change." This morning, when Sarah

went into camp, the refugee women were horrified. They immediately understood. Her shaved head is a sign of intense grief. For me it is also an image of cancer, of chemotherapy and impending doom. But Sarah has too much vitality for the image to rest on her alone. We all helped shave her head, and it is a symbol for us as a group.

March 19

An epidemiologist is here from the CDC in Atlanta, surveying the health problems here and in other camps. He gave us two boxes of U.S. Army C rations. The gift made us feel giddy, like an unexpected Christmas. Five of us sat down and divided up small cans of tuna, franks and beans, cheese, and chocolate.

We talked with the epidemiologist about the lack of medical leadership from the Sudanese or UNHCR and how costly this has been in the entire program of relief. We told him about running out of chlorine, and how futile it was treating diarrhea and then letting refugees drink the same foul water.

He said that the Sudanese are worried that the refugees will somehow pollute the water supply even worse, and he told us a bizarre story about the top health official, who is preoccupied with the amount of feces the refugees produce. At a recent health-policy meeting, the official described the amount of stool that an entire camp will produce in a day or a week or a month, calculating from the volume of stool one adult produces in a day. The astounding figures were put forth for debate, ignoring that the refugees defecate in fields away from the water, where the waste rapidly dries and only fertilizes the fields.

The epidemiologist says that the initial weekly death rate in Fau 3 is the highest that he has ever seen, one and a half times the death rate in the worst Cambodian refugee camp at

the worst time. In less than two months more than 3 percent of the camp population has died- 505 people, mostly children. He says that starvation during the civil war in Biafra in 1969-70 was also quite severe, but the data from there is fragmentary. If the epidemiologist is right, perhaps the all-time world record belongs to Fau 3.